Here in Seattle, people make pilgrimages to Bruce Lee’s gravesite to pay homage to the icon. Across cultures and religious traditions, burial sites have long held a place of honor, both to celebrate the deceased and to provide a place for the living to “visit” them. Which is why America’s history of segregating the dead is so troubling.

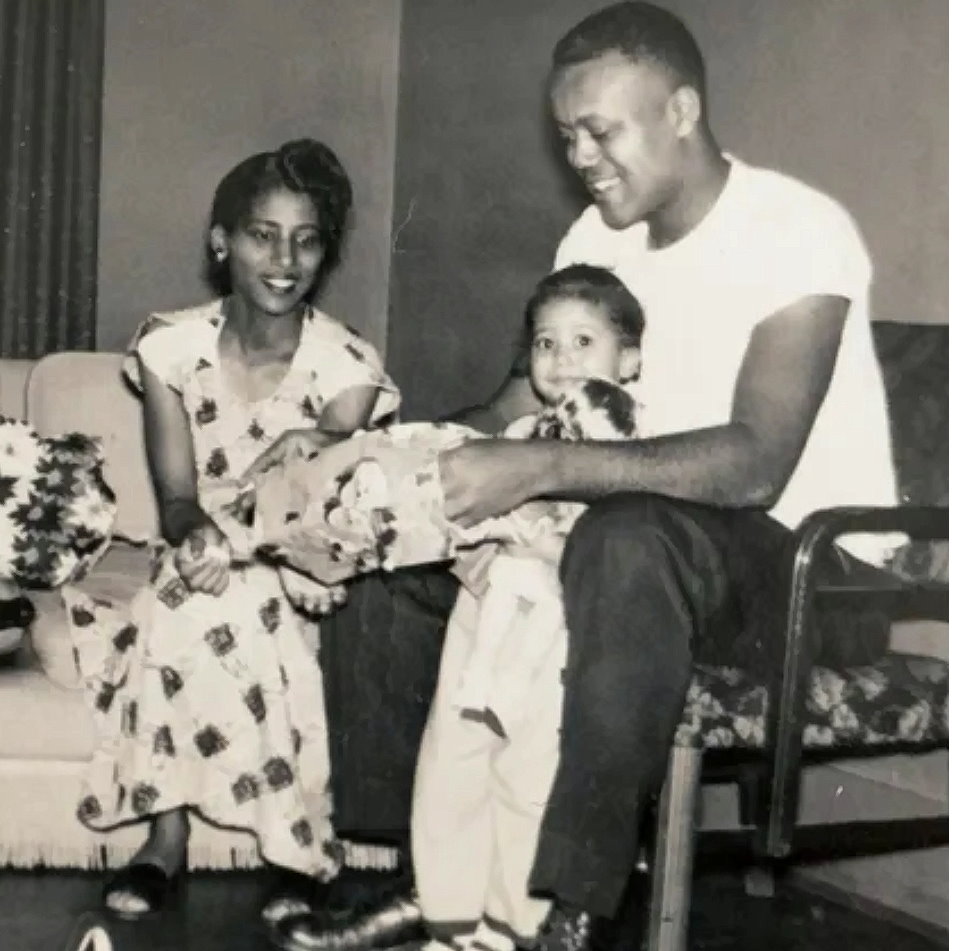

Segregated graveyards are a flashpoint for civil rights. In 1957, 3.5-year-old Milton “Buster” Price, Jr. died of drowning in a neighbor’s unfenced swimming pool. After a long legal battle, his parents were barred from burying their son in North Seattle’s Evergreen Washelli Cemetery because he was Black. Following this ordeal, they laid their son to rest at Lake View Cemetery, coincidentally home to Bruce Lee’s grave.

During slavery, most plantation owners required the racial segregation of cemeteries on their property. Slaves were often not allowed to bury their own dead. Now, cemeteries separate people based not just on race, but also on religion, past military service, and financial ability. So, what motivates us to separate our dead?

Segregating the dead

From strict racial rules on housing and employment to the literal segregation of the dead, the effects of America’s long, deplorable history of racism remain today, despite segregation “officially” being outlawed.

As might be expected, there are countless cemeteries in the South that were segregated under the Jim Crow laws. Yet, this bizarre tradition was by no means limited to Southern states. In fact, the racial segregation of the dead was one form of racism that was normalized throughout the country, from New York to Michigan to Washington. And many of these norms of segregation remained in place even as other forms of segregation were officially struct down as illegal.

Throughout the 50s and 60s, the families of black and indigenous soldiers who died fighting for the US were forbidden from burying their deceased in certain cemeteries. As recently as 1996, a church in Georgia attempted to have a baby exhumed from its cemetery because the baby’s father was Black.

While courts eventually struck down many of these attempts, the fact that cemeteries still felt emboldened to reject people based on skin color speaks volumes.

Segregating the living

In terms of population segregation within cities, there is no neat Mason-Dixon Line divide. America’s most segregated cities are in the North and the South, in the East and the West, and in the Midwest. Segregation’s long, poisonous tendrils have left an indelible mark across the country. Even in more “progressive” places where racial equality is the stated goal (at least, according to the well-spoken politicians), segregation is not so easily eradicated.

New York City has been learning that lesson. Under the previous administration of Mayor Bill de Blasio, an effort to increase affordable housing in the city was found to only acerbate a deep-rooted racial divide. This despite the fact that the Fair Housing Act, passed in 1968, was meant to end discriminatory housing practices; NYC passed its own version of that law, the first of its kind, in 1951.

Real estate has a long history of legal workarounds to segregation, particularly “racial covenants” that barred people of color from owning property in certain areas. This type of covenant was common in cities from Boston to Seattle. Only in recent years have states started enacting laws that allow homeowners to get rid of these racial covenants. Today, non-white homeowners are still forced to have racially exclusionary language removed from modern house deeds.

In Seattle, there are literally dozens of neighborhoods – encompassing roughly 20,000 properties – that followed this practice. As recently as 1948, at least one subdivision was marked as “Aryan only.” It’s all but certain unsuspecting homeowners will be unearthing this discriminatory language in their deeds for years to come.

Ongoing segregation isn’t just a byproduct of old laws, though. In 2019, an extensive investigation by Newsday found that Long Island house hunters of color – particularly African Americans – still faced discrimination from real estate agents and brokers. Often, they faced financial barriers that their white counterparts didn’t. Segregation might not technically be a legal standard anymore, but human bias ensures it remains in practice.

Religion and Segregated Burial

Segregation continues to follow some people from birth to the grave. In many religions, that segregation is apparently meant for the afterlife too.

In the West, religious institutions, particular Christian, have long been among the most important in upholding racial hierarchies, particularly through segregation.

Most Christians believe in hell. Perhaps they believe that their orderly catacombs will fast-track those within for entrance into the Pearly Gates. And yet, Jesus said, “I tell you, my friends, do not fear those who kill the body, and after that have nothing more that they can do” [Luke 12:4]. After death, the soul is in the hands of God, regardless of where they are laid to rest. Therefore, if these segregated burial sites are not for the dead, then they must be purely for the living.

Hate groups target Muslim and Jewish cemeteries for vandalism, a gross and effective kind of violence. People idolize their ancestors, so attacking cemeteries sends a strong message. If burial grounds were unsegregated, would we see this violence? Israeli officials have destroyed Muslim burial grounds to make room for other projects. This erases the history of Palestinians in the area, which is exactly the point.

Indeed, there is a lot of hullabaloo around keeping graves separate. Only recently, the Washington State Supreme Court overturned the case that kept Buster Price from being buried in the segregated graveyard. Even so, too little, too late is an understatement.

Many believe the categories that separate us in life also separate us in death. Do we believe that the afterlife is split into sections containing only people who are just alike? How lonely that must be. For generations, we have allowed segregation to deprive us of the unique pleasures and education that comes from racial integration. We are now, and until the end of time, Children of the Same Universe.